|

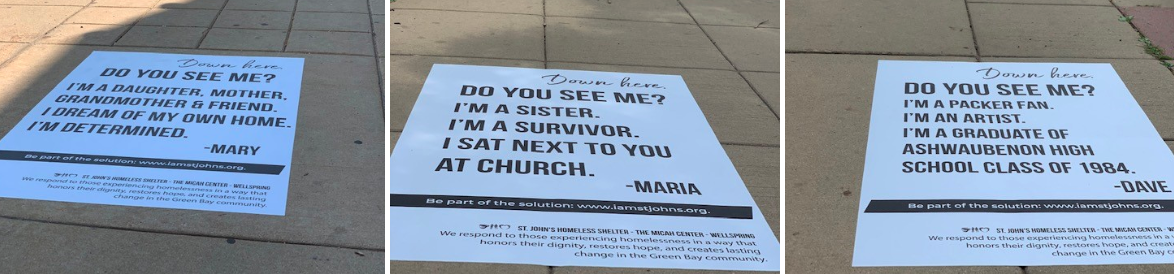

Nonprofit organizations tell stories about the people that they help to humanize their work. This can lead to greater awareness of the value of their programs and greater support. However, there can be a number of issues in how individuals receiving aid or support are depicted in those stories. This is the first of a series of blog posts about issues which arise when organizations share stories of those they serve. The focus of this post is how the individuals who show up in success stories are portrayed. To get a sense of how individuals in success stories are described, I Googled “social service client success stories,” and examined the first 35 that showed up in the search. These came from organizations in seven states serving those experiencing homelessness poverty, and domestic violence, ex-convicts, individuals with behavioral health problems, and immigrants. There was a familiar pattern in the stories. Individuals find their way to an organization which provides services or aid. The issues, problems, and challenges of these individuals are described with varying amounts of details. The services provided to those individuals are also recounted, in some cases with more specifics than others. The impact of the services on the client are described in some cases. Often, the clients are described as grateful after receiving the services/benefits. Here are several examples: “she has a renewed sense of hope;” “she is now working full-time;” “I never knew what a strong person I was until going through the program.” In reading the 35 brief descriptions, I saw two-dimensional pictures of almost all of those who were seeking services, as they were shown only in terms of their situation or needs. With one exception, there were not description of the strengths that these persons had before they had contact with the serving organizations. The one exception was about a former prisoner: "He really dedicated himself to this. To have spent all that time incarcerated, and then to spend all that time to stay true to the course and not turn back, that’s who he is. For other people, going through the same thing, for this amount of time, this experience may have crushed them. But, he persevered for himself and for his family. He is an ideal of what a man is—a family man— a father who does what it takes, the right way." For someone to be treated with dignity, as a person of value, one needs to be seen as an individual, not just a member of a racial or an ethnic group, and not defined by a label or stereotype. When people acknowledge that there are a number of things that make people who they are, when they recognize that individuals are more than their situation and their issues, then they are beginning to treat those persons with the dignity they deserve. The individuals in the stories were not being treated with dignity. How then to show more than a two-dimensional representation of individuals? Here are two examples of approaches, neither of which are common ways of telling stories. The first example (shown below), and this is not a factual story, comes from the charity War Child Holland, a non-profit which aims to protect children caught up in conflicts, support their education, and equip them with skills for the future. This video shows an eight-year-old Syrian boy, Kadar, in a dusty refugee camp with a superhero playmate. The second example is the “See Me” campaign from St. John’s Homeless Shelter in Green Bay, Wisconsin, in which eight images, each with the words of an individual experiencing homelessness, were placed on city sidewalks in the summer of 2019. Three of these images are shown at the bottom of this post. “The guests who come to St. John’s are so much more than a singular identity of ‘homeless.’ Each person is someone’s son or daughter, each person has hopes, dreams, and qualities that make them unique,” says Alexa Priddy, St. John’s Director of Community Engagement. Physicians in many countries historically have taken the Hippocratic Oath as a rite of passage for medical graduates. In its most common form, it starts with: “First, do no harm.” I believe that when non-profit organizations, in the service of describing their programs and raising funds, depict individuals receiving services as only the sum of their problems, they are doing harm. This practice can further negative stereotypes of those in need. As is shown by the examples shown above, we can do better.

0 Comments

How do you connect with an audience that may be skeptical to the message which may come through as you use stories for awareness and/or advocacy? This is the second post on connecting with audiences, a follow-up to a post from June, 2019, in which I wrote on how to connect to audiences that are likely to be more receptive.

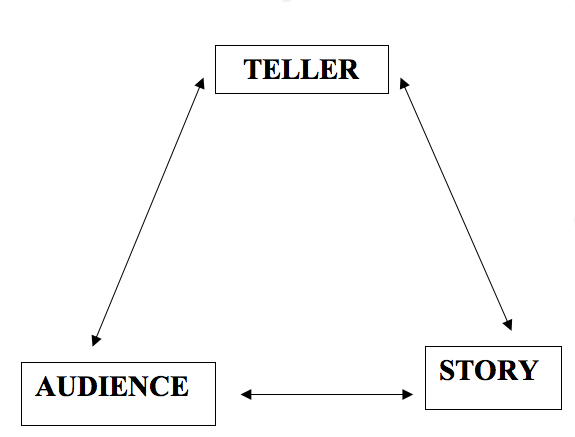

Connecting with an audience with individuals who are skeptical or who have beliefs that may be counter to yours is a daunting challenge. Once we have an opinion or belief about an issue, we tend to not pay attention to or give credence to information that contradict our position. Cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber call this myside bias,1 a type of confirmation bias, the cognitive process that leads people to either reject interpretation that goes against their beliefs or to interpret the information in a way that confirms these beliefs. Presenting information to change beliefs can lead to the backfire effect2 in which people may react to evidence showing that their beliefs are incorrect by strengthening their original position. When presenting information is not successful, stories may be. According to Michael Dahlstrom, there are two contrasting ways in which information is processed. As humans are natural storytellers, humans process information predominantly though narrative pathways, a more natural, efficient, and easy ways to process the information. He contrasts this with scientific processing, which is more challenging and requires analytical thinking skills to weigh, value, and make sense of the information. Dahlstrom uses the controversy over the safety of vaccines to show how these pathways compete: Vaccine proponents, he explained, often rely on scientific evidence to communicate the message that vaccines are a safe and effective way to prevent disease, whereas members of the antivaccine movement often share stories about dangerous side effects experienced by vaccinated children, which are processed as natural narratives.3 In the previous blog post, I mentioned three factors of a story and the way the story is told/communicated that are essential for the story to connect with an audience: Clarity: Is the story clear enough for the audience to understand as they experience it? Resonance: This includes emotional resonance (connection to emotions that matter to the audience), intellectual resonance (credibility), and what the marketer Debra Louison Levy refers to as “echo”—whether the narrative is similar in some way to others that are already part of the audience’s sense-making narrative. Something happens: Stories do not always have to be about overcoming conflict, but something has to happen. If there is learning/understanding or actions following this learning or climax, the story is more likely to “stick.” In addition to clarity, resonance, and something happening, stories in which there is a plot twist or an unexpected shift in the story may be more memorable. You see this in the memorable Agathe Christie novel, Murder of the Orient Express, made into a movie in 1974 and again in 2017, in which Detective Hercule Poirot finally realizes the question is not “Who done it?” but “How and why did a dozen passengers commit the murder?" I experienced the nature of the story shifting when I was I listening to a keynote speaker at a 2018 Poverty Conference. C. Nicole Mason, the dynamic Executive Director of the Center for Research and Policy in the Public Interest at the New York Women’s Foundation, was talking about her early life, growing up a in chaotic low-income single-parent family in Southern California. As I listened, I thought that this was going to be a rags to policy wonk story, about how she had made it to where she is today through her hard work and determination. Then she said: “Growing up, I knew many kids in my neighborhood who were smarter and more capable than me, and they didn’t make it out. Many of them have been killed, gone to prison, are living hand to mouth or otherwise on the margins of society. Should we blame them or the system that only allows a few of us at a time to escape?” She had changed the focus from her life as a singular example of how one can rise from poverty to a systemic examination of how the barriers, difficulties, and oppression in some communities make it hard for even smart and capable young people to be successful. In the terms of the FrameWorks Institute, she had changed the lens from portrait, a tight focus on an individual to landscape, viewing individuals in the context of their environment. Here is one approach to connecting with a skeptical audience. From time to time, I give story-based talks on poverty and homelessness to Christian education sessions at suburban churches in Southeastern Wisconsin. I recently read Ms. Mason’s 2016 memoir Born Bright: A Young Girl’s Journey from Nothing to Something in America 4. As I was reading this, I thought about how I might use Ms. Mason’s words and story in talking to an audience where everyone is “not singing from the same hymnbook.” There is a triangle, a three-part relationship which oral storytellers use to describe the connections between the teller, the story itself, and the audience. For an oral story to be effective, all of these connections need to exist. The teller needs to be emotionally connected to the story—there is something in the story that produces an emotional link. In addition, audience members need to be able to find common ground on some level with both the story and the teller in order for the story to resonate with them. In the section of Laura Packer’s book From Audience to Zeal: The ABCs of Finding, Crafting, and Telling a Great Story5 on connecting with an audience, she writes: “Love them where they are. If you love the audience in their current state, you are more likely to be able to connect with them.” While this applies obviously to the audience of an oral storyteller, I believe that it is also fits both to writing for and talking with a skeptical audience. When we think of an audience as composed of individuals whose opinions are wrong and need to be corrected, one is likely to preach to rather than connect with the audience. When we think of the audience as composed of people who are like us in some ways, we have a greater chance of connecting with them. Returning to my talking to a Christian education class in relatively affluent suburbia, in starting where the audience is, I might share my reaction to Ms. Mason's book. I would say that she had put her individual story in the context of the environment in which she grew up, in which the risk factors for minority youth were high, and the supports were minimal. As the Framework Institute points out, “If individual cases are not embedded in a larger social story, the public will see an issue as a private rather than a public problem, dismiss the importance of preventative approaches, or simply fail to imagine collective solutions.”6 I would also say that Ms. Mason’s success had much to do with the fact that from a young age she loved school, found it both a safe and nourishing place, even when the teaching was subpar and the resources inadequate. She won several awards for her writing and speaking through her school years and impressed and connected with teachers who mentored her, nourished her, and advocated for her. She was “born bright” and she worked hard, but her intelligence and efforts could easily have led nowhere, if not for a high school counselor with strong connections with Georgetown University. At that point, I would apply the “Yes, and…” technique from Comedy Improv, in which one agrees and then adds something to the discussion. Given that we understand stories through the lens of our own ideology and worldview, a politically conservative individual hearing Ms. Mason’s might think: “She’s the exception that proves the rule.” I would add my opinion that working hard is essential in doing well in any circumstance, and when we encounter situations in which smart, capable children who work hard have trouble succeeding, we need to see what can be done that raises the odds that they will become smart, capable adults. Yes, individuals have to work hard, and there are societal factors that can make that very difficult. Michael Dahlstrom7 states that previous research suggests that narratives may have a stronger effect on the acceptance of novel information over altering preexisting information. When we do not challenge an audience’s view of the world but rather suggest that an additional perspective is also needed (Yes, and…), I believe that the chances of our communication having an impact will improve. REFERENCES 1. Mercier, Hugo, and Sperber, Dan. (2019). The Enigma of Reason. Boston: Harvard University Press. 2. Effectivology. (2019). The Backfire Effect: Why Facts Don’t Always Change Minds. Retrieved from https://effectiviology.com/backfire-effect-facts-dont-change-minds/ 3. Dahlstrom, Michael. (2018) Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Understanding Narratives for National Security: Proceedings of a Workshop, pp. 13-19. 4. Mason, C. Nicole (2016) Born Bright: A Young Girl’s Journey from Nothing to Something in America. New York City: St. Martin’s Press. 5. Packer, Laura S. (2019). From Audience to Zeal: The ABCs of Finding, Crafting, and Telling a Great Story. Tolleson, AZ: The Small-Tooth-Dog Publishing Company. 6. Neil, Moira, et al. (2016) Strengthening the Support: How to Talk about Elder Abuse. A FrameWorks Message Memo. Washington, DC: The FrameWorks Institute. 6. O’Neil, Moira, et al. (2016) Strengthening the Support: How to Talk about Elder Abuse. A FrameWorks Message Memo. Washington, DC: The FrameWorks Institute. 7. Dahlstrom, Michael. (2010). The Role of Causality in Information Acceptance in Narratives: An Example from Science Communication. Communication Research, 20(10), pp. 1-19. I posted last year about the importance of matching stories with audiences. I am continuing this theme, focusing on elements that lead to stories connecting with audiences, starting with audiences that are likely to be more receptive to the story or a message behind the story. If a story is told or shared to entertain an audience, the primary measure of success might be the degree to which the audience enjoyed the story. However, if a story is told or shared for the purpose of advocacy or awareness, in order to be considered successful, it first has to connect with an audience and then make an impact on some members of that audience, producing some change in beliefs, attitude, or action. I think that it is useful to look at the triangle which oral storytellers use to describe the connections between the teller, the story itself, and the audience. For an oral story to be effective, all of these connections need to exist. The teller needs to be emotionally connected to the story—there is something in the story that produces an emotional link. In addition, audience members need to be able to find common ground on some level with both the story and the teller in order for the story to resonate with them.

For any audience, regardless of the medium, there are criteria which can be used to determine the strength of the connection between a story and audience:

In addition, if a story is told for the purpose of advocacy or awareness, there needs to be an “Ask.” If, at the end of a story, there is not an Ask—if individuals or groups watching or listening the story are not asked to do something such as take action or change the way one thinks about an issue—then the story can only be appreciated as interesting or even dismissed entirely, and there will be no lasting impact. Recently, I went to a lecture in the informal setting of a barn on a farmette. The speaker was Cindy Crosby, a steward supervisor for the Schulenberg Prairie at the Morton Arboretum in Illinois and a writer, teacher, and lecturer on the tallgrass prairie and nature conservation. She spoke about how prairies once covered 40% of this country, and now it is only 1%. She intertwined the story of prairie loss and the importance of prairies with her own story about how a general fascination with nature and the outdoors has led to her becoming an educator and advocate for tallgrass prairie preserves. The lecture was filled with anecdotes, some scientific information, history, and humor. There were about thirty of us gathered for that lecture. One person who followed Cindy’s weekly blog had driven two hours to listen and to meet her. He was the only member of the audience actively involved in stewardship of a prairie. Several people had come because they were very interested in turning part of their yards or property into prairie, and others simply because the topic or the idea of a lecture in a barn were intriguing. How effectively did she connect with her audience? Based on the high percentage of those attending who bought books and the buzz of conversation after the lecture, the answer would be that she was successful. Using the TELLER-STORY-AUDIENCE triangle, Cindy Crosby had accurately read the audience as people who were interested but not knowledgeable. She was personable, and the few times she used technical language she readily clarified the terms. Instead of explaining prairie plant roots in scientific terms or measurements, she invited two children from the audience to stretch a piece of yarn to its 18 foot length. Illustrating the enormous depth of the root in a way that enlivened the lecture. Her description of the joy and wonder she experienced while walking through a prairie connected with the emotions of the audience. We wanted to be there in those moments, watching the movement of the tall grass in the wind, marveling at a dragonfly. Cindy also had a very soft Ask, which was well received. She invited us to learn about the life prairies, to visit prairies near us, and suggested that we plant a small section of our yards with prairie plants, helping us to visualize the butterflies and birds that might visit our yards if we did. One thing that contributed to the success of her talk was that we were a self-selected audience, coming in with some interest in the topic and predisposed to be open to learning. Connecting with an audience that was receptive was certainly easier than speaking to a group of people who see a prairie as a collection of weeds, with nothing about the prairie that a John Deere tractor, seed corn, and fertilizer could not fix. Connecting with an audience whose views are greatly different than, or perhaps antagonistic to, the awareness or advocacy message one is promulgating is certainly more difficult than connecting with a friendly and receptive audience. In the next blog post, I will address how one communicates with and connects with a less receptive audience. The only sporting events I watch on television are college basketball games, especially when the NCAA championship tourney rolls around in March and April. The 2019 tournament was a good one, with a number of games coming down to the last minute or last several seconds. This was especially true for games played by the University of Virginia team, which barely won several games as they advanced through the tournament and clinched the championship in a back and forth game with Texas Tech University. When I went online to read the analysis of the game the next morning, I was surprised to see a reference to storyteller Donald Davis. Now, Donald Davis is a preeminent national storyteller, with numerous books and recordings. When he performs at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee, telling stories about growing up in mountainous western North Carolina and about life in general, he performs in one of the big tents that seat 1000 people, and there is standing room only. The University of Virginia basketball team had suffered an embarrassing loss the year before, when they were the first top-seeded team in the NCAA tournament history to lose to one of the lowest seeded teams. As Tony Bennett, the coach of the team, was agonizing over how to help the team recover from the loss, his wife Laurel remembered hearing a TED talk by Donald Davis in Charlottesville four years earlier, How the Story Transforms the Teller. In that talk, Davis recounts his own father’s story of having suffered a crippling injury as a five-year-old, one which meant he would never be able to do farm work. His mother insisted that he tell the story over and over again—from his point of view and what he learned from it, from the doctor in Atlanta who saved the boy’s leg and what he learned, from the parents’ perspective. She insisted that he tell it over and over, because, in her words: “When something happens to you, it sits on you like a rock. And if you never tell the story, it sits on you forever. But as you begin to tell the story, you climb out from under that rock and eventually you sit up on top of it.” Davis goes on to say in the TED Talk that telling and retelling the story of the unfortunate things that have occurred do not change what happened, but the story has the remarkable power to completely change our relationship to what has happened. Coach Bennett showed the YouTube clip of that TED Talk to his team on their first practice, so that they would not continue to wallow in pity but instead reflect on what they could take from the loss and talk publicly about this. He credits the talk and their discussion of it as one the things that helped individual players and the team. Here’s the TED Talk:

I was co-presenting the workshop “Framing Stories for Social Change” at a regional storytellers’ event in April of this year. The workshop focused on the use of digital stories for promoting change and awareness, a theme that I have written about in this blog. The audience was primarily oral storytellers, professionals who are paid for their performances and others who use storytelling in their work or life. While there was interest in the use of personal digital stories, there was more interest in how stories told orally could be used to make a difference.

This blog post is an initial attempt to answer that question, focusing on my own experience. Before getting into this, I want to touch on the “storyteller’s magic.” There is something special about telling a story to a live audience, because when the story and the telling is working, the individuals listening are very present and engaged. I was talking several weeks ago with Kay Weeden, a bilingual storyteller who used to be a middle-school teacher. She was talking about the first time she told a story in her class, and how suddenly students started to really pay attention. A similar thing would happen when I was teaching social work students in college. In a class where some people looked distracted, when I switched to the storytelling mode every eye would be focused on me. That’s not to say that any time anyone sets out to tell a story, there will be rapt attention from an audience. Stories need to be well-constructed with a beginning and an end, although not necessarily follow a linear timeline. They need to be about something. Jay O’Callahan, the superlative New England storyteller, says that stories are about people and places and troubles. Kendall Haven, in his 2014 book Story Smart: Using the Science of Story to Persuade, Influence, Inspire, and Teach, gives a succinct definition of a story: “a narrative account of a real or imagined account of an event or events.”1 Haven also states that for a story to be effective, there needs to be sufficient relevant detail to make it seem real, vivid, and compelling. When these components are present, and the teller is skillful, good things can happen. In telling stories to promote change or raise awareness, the goal is not just to hold an audience’s attention but also to help them think about an issue or a group of people in a different way, and perhaps to take action. My first experience of attempting to use stories for awareness was through the Wisconsin Humanities Council, which funded a story-based presentation I gave on poverty and homelessness in the Great Depression and the present. A researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh shared stories with me of people who had lived during the Great Depression in Oshkosh, oral histories gathered by his students in interviewing older adults. I paired these with my experiences from working for nine years in a shelter for homeless families in Southeastern Wisconsin. For the current stories, I would take the persona of the person experiencing homelessness whose story I was telling and tell it more or less in their voice. I would then step back and talk about it from the perspective of a social worker and professor. Over an eight-year period, through the Wisconsin Humanities Council Speaker’s Bureau and other invitations, I gave that presentation more than twenty times. How well did it work? I really don’t know. I know that I had the audience’s attention while I was talking. There would be discussion afterwards, more in some venues than others. There was no systematic or unsystematic evaluation. When I put the talk together and presented it, I did so without thinking much about how to address an audience that might be skeptical. I also did not know then what I do now, about the importance of framing a story. The Frameworks Institute. has conducted research on the difficulty of communicating with the general public about homelessness. The research was in the United Kingdom, but I believe that the findings and recommendations can be applied to this country. Their analysis showed that that people see homelessness as divorced from larger economic forces, and being homeless is seen as an individual rather than a collective problem. The Frameworks Institute recommends that organizations working in this area define homelessness in the context of the large group of people whose fragile economic status puts them at risk of being homeless. They counsel that stories that are told of individuals should be in the context of systemic causes which have systemic solutions, and these solutions can lead to positive societal consequences. Connecting the stories with commonly held positive values can lead people to consider homelessness as something other than personal failure. I am currently putting together a story-based 35-minute piece that I will be presenting at least three times in the fall of 2018 in Wisconsin. I draw on my experiences living in El Salvador as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the early 1970s and in conducting research on youth and migration from 2005 to the present in that country. I also bring in stories of people I know, recent immigrants from Latin America to Wisconsin. In this presentation, again drawing on the work of the The Frameworks Institute , I am attempting to link the reasons for immigrating to the United States with commonly held values, like our shared humanity. I will draw connections between newcomers to this country and my ancestors, who came to this land more than 375 years ago. My goal is to not come across as a figure of authority but someone who is sharing stories that are important to me, in the hopes that the presentation will be a springboard for discussion. How can I tell if these presentations/discussions have been successful? It will be hard to determine. Talking to community groups is not like conducting a research study, where one can conduct pre-tests and post-tests. One indicator could be the amount of discussion generated from the presentation, but that is hard to quantify. From my point of view, being able to tell if these stories and this presentation have shifted attitudes or beliefs is not the point. Certainly, I would be pleased if individuals coming to the presentation with a negative view on immigration came away with more nuanced opinions. But mainly, I want to spark discussion and communication. I want to listen as well as talk. That is something that those who live in this country are not doing very much these days. And if through stories, which captivate attention and aid one in understanding the situation of others, I have laid the groundwork for talking with each other, I will be pleased. 1 Haven, Kendall (2014). Story Smart: Using the Science of Story to Persuade, Influence, Inspire, and Teach. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, p. 11.

When advocacy groups and nonprofit organizations reach out to the public, an important first step is answering the question “Who is my audience?” It is not possible to effectively communicate with everyone. Information, messages, and stories that resonate with one group of people may not resonate with others. Identifying key audiences allows an organization to choose and shape what is shared.

Figuring out “Who is my audience?” is usually presented as a linear process: identify those you want to reach, find out as much about them as you can, and then tailor your communication so that it not only reaches this group but may inspire them to support your cause or organization. Organizations and advocacy groups often use stories in their communication with key audiences. As I have written about at other times in this blog, we respond more fully to individuals’ stories than we do to facts and information, engaging more emotionally and with more parts of our brain. However, when it comes to the use of personal stories from those affected in some way by an issue, the process may be different than the linear one described above. In the digital storytelling model pioneered by StoryCenter, individuals tell and create their own stories, each in their own voice. When I conduct three-day digital storytelling workshops using this approach, I invite participants to: “Tell a story that is important to you, a story that only you can tell.” When groups use stories to make a point, often they make the stories of participants/clients fit a predetermined message. If groups or organizations have access to individual personal stories that are powerful, rather than trying to make the stories fit the message of the organization (like Cinderella’s stepsister attempting to fit a size 11 foot into a size 7 glass slipper), a better approach would be to ask, “Which groups or kinds of individuals would be responsive to this story?” I came across the digital story “Mr. Sunday” on the website of Creative Narrations. In this story, Marco Dominguez’ tells of his decision to leave his position in a college to teach public school, and the meanings of his presence to his public school Latinx students. For me, his story skillfully illuminates the importance of students having a teacher they can identify with, especially when teachers who look like them are few. I received permission from Marco to share his story on this blog. As I asked myself: “Who are people I know who would benefit from hearing this story?” the names and faces of the people who came to mind were individuals who are already sympathetic to this issue, but are not involved in diversifying the educational experience of underrepresented groups. I am not sure that others I know, people who are more conservative on immigration policy, would react positively to this digital story. As we are living in a very divided country, it is important to reach out to those who may not necessarily agree with you, and it also essential to communicate with those who may be on your side. “Preaching to the choir” is seen as a negative, but in my opinion this is only problematic when one’s efforts go into convincing those who are already convinced. Preaching to the choir can be effective when your aim is to convince people who are already on your side to take action. If this video were to be shared with individuals with sympathy for this issue, for the digital story to have the desired impact, it is necessary to “make the ask,” to clearly state what you want the audience to do. When I first started working on political campaigns, I learned the importance of “the ask.” I was told a story about Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, a Massachusetts politician. This version of the story comes from the Boston College Libraries1 : O’Neill learned the importance of the ask in his first campaign for the Massachusetts state legislature. On the last day of the campaign, Mrs. Elizabeth O'Brien, his high school teacher who lived across the street from him, approached the aspiring politician and said, "Tom, I'm going to vote for you tomorrow even though you didn't ask me." O'Neill was puzzled by her response. He had known Mrs. O'Brien for years and had done chores for her, cutting grass, raking leaves and shoveling snow. He told his neighbor, "I didn't think I had to ask for your vote." She replied, "Tom, let me tell you something: People like to be asked." People like to be asked, and it is also true that if you do not directly ask someone to do something—take action on an issue, support a cause or organization—they very well may not do anything. We are bombarded with information. A 2009 study suggested that 34 gigabytes of content and 100,000 words of information crossed our eyes and ears every day.2 By now, it must be more. We react passively to most of this. When individuals are asked to respond to something, even if they decline to do so, the act of making that choice means that they are more engaged. Stories can be an important tool in challenging people to get involved and lend support, when we choose stories to share with an audience where it is likely that the seeds of the story will fill fertile ground. And when you do that, make sure that you include the ask. 1 https://www.bc.edu/libraries/about/exhibits/burnsvirtual/oneill/4.html 2https://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/12/09/the-american-diet-34-gigabytes-a-day/

As humans, we respond to stories. Roger Schank, a pioneer in artificial intelligence, wrote that we make sense of the world through the stories we tell and are told, and that the human brain is wired to understand, react emotionally, and retain information from stories.1

When we are exposed to a PowerPoint presentation, only the language processing part of the brain that decodes words into meaning is active. However, when we are told a story, not only are the language processing areas of our brain activated, but also other areas that we would use if we were experiencing the events—the sensory cortex if the way an object smells is described, the motor cortex if an individual in the story walks quickly.2 To some degree, we actually live the stories that we are told. Not only do we connect to stories on the level of our senses, we also relate on an emotional level to individuals’ stories. For those reasons, in advocacy and awareness work, we often use individuals’ stories to call attention to social and political issues and to generate support for organizations. A drawback to using individuals’ stories is that researchers have found that we are more likely to respond on an emotional level to the story of an individual than a story of many people. This may be because when we hear a story about one person, we can form a mental image of that person, and then we identify with that mental image. When we hear of a situation experienced by many, it becomes more difficult to form that mental image. Without that mental image, we care less. Joseph Stalin allegedly once said to U.S. ambassador Averill Harriman: "The death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic." In addition to the difficulty in responding emotionally to the situation of more than one person, another factor that comes into play is the concept of pseudoinefficacy. Efficacy, according to psychologist Albert Bandura, is having the ability or capacity to produce a desired result or effect.3 With a greater sense of self-efficacy, there is increased motivation to act or respond to a situation. In contrast to efficacy is pseudoinefficacy, a state in which when individuals are aware of many people in a situation that they cannot help, they often feel less good about helping those they can help, and they help less often. 4 Motivation to act or respond may be diminished when the numbers affected by a catastrophe or debilitated social condition increase, when individual stories coalesce into statistics. Researchers tested this hypothesis with an experiment in which participants in an unrelated research study were given a small stipend, and then given the opportunity to donate a portion of this stipend to a starving child in a developing country. One group was asked to donate to one particular starving child. Another group was asked to donate to one of two starving children. Fewer individuals in the second group opted to donate. When in a related experiment, a starving child was presented as one of many in that situation, there was even less willingness to help. 5 Pseudoinefficacy seemed to be operating in this situation. So how do we overcome the challenge of pseudoinefficacy? One approach would be to share personal stories that illustrate evidence-based approaches that have proven to be successful in addressing the issue, so that the listener/reader understands that actions can yield positive results. The authors of the study on pseudoinefficacy suggest that examples of personal efficacy might combat the feeling that no actions will have an impact. An illustration of this comes from Loren Eisley’s essay “The Star Thrower.” 6 Eisley describes a narrator walking along the beach at dawn when he sees a man who had stopped and was looking down at the sand. In a pool of sand and silt a starfish had thrust its arms up stiffly and was holding its body away from the stifling mud. "It's still alive," I ventured. "Yes," he said, and with a quick yet gentle movement he picked up the star and spun it over my head and far out into the sea. It sunk in a burst of spume, and the waters roared once more. ..."There are not many who come this far," I said, groping in a sudden embarrassment for words. "Do you collect?" "Only like this," he said softly, gesturing amidst the wreckage of the shore. "And only for the living." He stooped again, oblivious of my curiosity, and skipped another star neatly across the water. "The stars," he said, "throw well. One can help them." The narrator walks on, and after reflecting on our relationships to animals and the universe, returns to the beach to find the starfish thrower. He says, "Call me another thrower," and begins to toss the sea stars back into the ocean. Being aware of the complexities of communicating for advocacy, awareness, and generating support, we can demonstrate what approaches are effective and tailor our use of narratives. Stories, either fictional ones like Eisley’s star thrower or ones from real life, can be used to challenge the prevailing attitude that there is nothing that an individual can do while appealing to our better selves. 1. Schank, Roger. (1995) Tell Me A Story. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. 2. Paul, Annie Murphy. (2012, March 17), Your Brain on Fiction. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/18/opinion/sunday/the-neuroscience-of-your-brain-on-fiction.html?pagewanted=all&auth=login-email 3. Bandura, Albert. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Self-Control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co. 4. Vastfjall, Daniel, Slovic, Paul, and Mayorga, Marcus. (2015). Pseudoinefficacy and the Arithmetic of Compassion. In Numbers and Nerves: Information Emotion, and Meaning in a World of Data, Scott Slovic and Paul Slovic, eds. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press. 5. Vastfjall, Daniel, Slovic, Paul, Mayorga, Marcus, and Peters, Ellen. (2014). Compassion Fade: Affect and Charity Are Greatest for a Single Child in Need. PLOS/One. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100115 6. Eisley, Loren. (1969) “The Starfish Thrower” in The Unexpected Universe. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World. Note: This is the first of a series of blog posts on story and advocacy/social change. To read all of them, subscribe to the blog. Through my own work with families experiencing homelessness, through my participation as a board member in an organization that serves struggling and homeless families, and as someone who does public speaking on poverty and homelessness, I have tried to communicate the realities of families and individuals who are struggling economically these days without playing into common stereotypes of poverty and homelessness. And I find it hard. One approach is to tell stories about individuals experiencing homelessness or barely staying afloat economically. After all, humans are hard-wired for story. As Jonathan Haidt says: “The human brain is a story processor, not a logic processor."* We remember stories, while our eyes often glaze over when we see facts or statistics. However, using individual stories often does not work. Social service organizations frequently showcase success stories, demonstrating through an example that participation in a program can lead to a better life for this individual or family. Given that we understand stories through the lens of our own ideology and worldview, what often happens is that when politically conservative individuals hear a success story, a common response would be: “If that individual made it, why can’t everyone in that situation?” The success stories can be interpreted in ways that reinforce that American core value of individualism. Many people assume that if someone is not successful, they must be unmotivated and not working hard enough. I am a founding board member of the ecumenical nonprofit Bethel House, Inc. in Whitewater, Wisconsin (bethelhouseinc.org). We provide transitional housing for families experiencing homelessness and also engage in homelessness prevention. I have been working with the organization’s Executive Director to surmount the challenges of effectively communicating to the public the perilous situation that low-income working adults face, to show how the organization’s work with families is consistent with commonly held values, and to demonstrate that our efforts can make a difference. We are utilizing the work and research of The Frameworks Institute, an independent nonprofit organization which uses cognitive and social science research to empirically identify the most effective ways of reframing social and scientific topics (http://www.frameworksinstitute.org/). Central to The Frameworks Institute’s approach is changing the way a societal issue is viewed from portrait (focusing on an individual) to landscape (seeing the big picture). This wide-angle lens systems approach means connecting personal stories with the answers to questions such as: “What are the conditions responsible for the problem?” For understanding the situation of low-income working adults, we draw on a number of sources, including research from The United Way of Wisconsin (https://unitedwaywi.site-ym.com/page/ALICE). We approached individuals who in the past had received services from Bethel house, asking if they would be interested in telling a story about any part of their life before, during, or after experiencing homelessness. I offered to work with them to make a digital story** of their experience. The story, when finished, would be theirs to do with as they wished. When they finished the story, if, they wanted to give Bethel House the right to share it, we would then try to put their individual story in a societal context and perhaps highlight Bethel House’s involvement with them. I also stated that if they chose to make a story, regardless of their choice on who might see the story, the digital story would not divulge any names or show their or their family member's faces. So far, three individuals have come forward wanting to tell their story. All three wanted Bethel House to use their story (two of the three have been developed to date). One of the stories, “Recovering from the Recession,” can be viewed here. We are in the process of showing the two completed stories to community groups and gathering feedback to assess the response from a range of viewers. It’s a good process. In showing the stories, discovering how they are interpreted and what impact they have, we hope to not only help people understand societal dimensions of homelessness but also to get better at telling stories in context. * The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion, New York, Pantheon Books, 2012, p. 281. ** Digital stories are personal stories, usually less than four minutes long, narrated by the person telling the story, usually including photos, video, and a soundtrack. They can be shared on YouTube or other platforms.

I took a workshop from Minton Sparks, an amazing storyteller/performance artist earlier this year. Her website description (http://mintonsparks.com/) is apt: “Minton Sparks fuses music, poetry, and her intoxicating gift for storytelling to paint word pictures of the rural South that put you square in the middle of the people and the places she knows like the back of her hand.” Her workshop centered around two questions: “Where are you from?” and “How does where you are from inform the definition of who you are?” After some introductory exercises, we each spent time developing a personal narrative based on George Ella Lyon’s poem “Where I’m From”*. That poem uses the repeating opening lines of “I am from….” Here is a part of the poem: I am from the dirt under the back porch. (Black, glistening, it tasted like beets.) I am from the forsythia bush the Dutch elm whose long-gone limbs I remember as if they were my own. It’s a good exercise, and I recommend writing your own version of “I Am From.” I was one of many workshop participants who stated that in the writing process, aspects of our lives became clearer. For me, it was a deeper appreciation of my early years. Here is what I wrote that morning: I am from a mother who was far more adventurous in her early life that we knew, and we could have figured that out if we were paying more attention. I am from a house in which Dad could often be found grading papers at the kitchen table, a father who talked a lot but could only express his emotions in writing letters. I am from the wood lot next door where Brother Dave and I played knights, with fallen dry limbs from the huge beech trees as swords. We were lucky that when those swords were struck together in our play mortal combat, none of the chips that flew put an eye out. I am from summers playing outdoors in the neighborhood when we were children, leaving the house after breakfast until Mom called us by ringing a bell. After lunch, outside again until the bell for dinner rang. I am from playing baseball and football in the only place flat enough to play in that foothills of the Appalachia neighborhood. Really enjoyable, though I wasn’t much good at either sport. And, because of my lack of skill and heft, I did not play organized football, so there are not concussions on my medical record. I am from not making a Little League team, having inherited from my parents my height and brain cells that work pretty well, but subpar reflexes and coordination. I am from books, my dad building a new bookcase every year, being read to when young, reading them myself when I was able—the Hardy Boys and Tom Swift, and on my 10th birthday, the book Gods and Heroes, containing the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Greek myths—743 pages long. I am from King College, where Dad taught, three blocks from our house, and visiting his first office in the basement of the Hay Building, where I could buy the coldest small bottle of Coca-Cola from the vending machine for a dime. I am from First Presbyterian Church, the old church downtown, not the new one built later farther out, which one of my children called a castle. I am from skipping Sunday School and church and going instead to Bunting’s Drug Store, where William Faulkner once lived upstairs, devouring ice cream sundaes. I am from not quite fitting in, tall and skinny and glasses that were thicker each year. I am from visiting our grandmother and relatives in Massachusetts in the summers, from seeing my 17-year-old cousin Wink, with his 1954 MG TD, a guitar, and long hair for that time, and realizing that there was another way to live outside of what I had known growing up in Bristol, Tennessee. I am from, and I realized this much later, that incredible sense of security from never having been evicted or parents being unemployed, growing up in the same house since I was three years old, always with food in the house, and my mother saying when my brother and I were teenagers that she did not need a light on in the kitchen, because the refrigerator door was always open. * Teachers and librarians have used this poem in schools and other venues. This is a collection of 73 poems inspired by “Where I’m From” collected by the Kentucky Arts Council: http://www.georgeellalyon.com/where.html Digital stories are short personal stories, written and narrated by the person who experienced them, and told with photos, sometimes video, and a soundtrack. They can be shared on streaming platforms like YouTube or Vimeo. You can find a number of digital stories on this blog. Locative digital stories add another dimension. They are site-specific stories which can only be accessed on one’s smartphone or tablet while the viewer is within 100 feet or less of the place where the story took place. It provides for a different kind of connection. Reading a story can “transport” you away from the physical space in which you inhabit. Last September, I was on an airport bus heading from Wisconsin to Chicago, reading a novel that took place in wintry Maine. A noise startled me, and when I looked outside, I was surprised that there was no snow on the ground. In contrast, instead of transporting you away, a locative story can make you feel more connected to where you are. Locative stories can reveal the “invisible landscape” of a place, not apparent on its surface, or on a map, or in a history book. They reveal a personal history of the space, a sense of experiencing it through someone else’s eyes at another time. In 2017, I developed five locative digital stories in the small city in which I live, Whitewater, Wisconsin. The project was funded by the First Citizens State Bank of Whitewater and made possible through the StriveOn app (available free through the Apple App Store or Play Store). StriveOn allows users to access uploaded videos, photos and other information when at specific GPS coordinates. Choton Basu, the developer of the StriveOn app, states: “Our belief is every place has a story. We’re working with communities to tell their stories (www.striveon.io).” One way to view the five digital stories is by walking on a 2.3-mile loop in Whitewater that goes past all the sites. The stories include a millennial talking about the scary stories he heard as a child of a “haunted” water tower in a city park, a mother telling about how the community rallied to build a state of the art youth baseball field to honor her young son who was killed by a drunken driver, a late middle-age woman recounting how meaningful were the trips she took as a child to the public library, and a bank president proudly describing the role of the bank throughout the city’s history. Perhaps my favorite is titled Mastodon Bone in Whitewater, a long-time resident about my age telling a story that was told to him when he was young by his father, about the origins of a giant bone that was found during a construction project. I smile as I remember the story every time I drive by that spot. Here it is: |

Storying the Human Experience

Yes, it's a grandiose title. But, as Flannery O'Connor once said, "A story is a way to say something that can't be said any other way." Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed