|

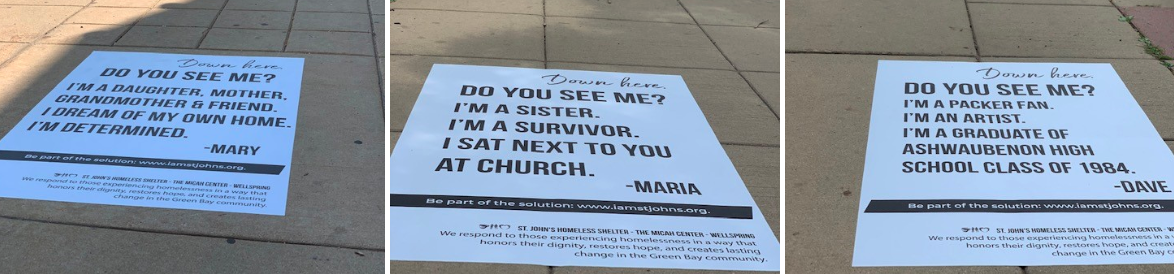

Nonprofit organizations tell stories about the people that they help to humanize their work. This can lead to greater awareness of the value of their programs and greater support. However, there can be a number of issues in how individuals receiving aid or support are depicted in those stories. This is the first of a series of blog posts about issues which arise when organizations share stories of those they serve. The focus of this post is how the individuals who show up in success stories are portrayed. To get a sense of how individuals in success stories are described, I Googled “social service client success stories,” and examined the first 35 that showed up in the search. These came from organizations in seven states serving those experiencing homelessness poverty, and domestic violence, ex-convicts, individuals with behavioral health problems, and immigrants. There was a familiar pattern in the stories. Individuals find their way to an organization which provides services or aid. The issues, problems, and challenges of these individuals are described with varying amounts of details. The services provided to those individuals are also recounted, in some cases with more specifics than others. The impact of the services on the client are described in some cases. Often, the clients are described as grateful after receiving the services/benefits. Here are several examples: “she has a renewed sense of hope;” “she is now working full-time;” “I never knew what a strong person I was until going through the program.” In reading the 35 brief descriptions, I saw two-dimensional pictures of almost all of those who were seeking services, as they were shown only in terms of their situation or needs. With one exception, there were not description of the strengths that these persons had before they had contact with the serving organizations. The one exception was about a former prisoner: "He really dedicated himself to this. To have spent all that time incarcerated, and then to spend all that time to stay true to the course and not turn back, that’s who he is. For other people, going through the same thing, for this amount of time, this experience may have crushed them. But, he persevered for himself and for his family. He is an ideal of what a man is—a family man— a father who does what it takes, the right way." For someone to be treated with dignity, as a person of value, one needs to be seen as an individual, not just a member of a racial or an ethnic group, and not defined by a label or stereotype. When people acknowledge that there are a number of things that make people who they are, when they recognize that individuals are more than their situation and their issues, then they are beginning to treat those persons with the dignity they deserve. The individuals in the stories were not being treated with dignity. How then to show more than a two-dimensional representation of individuals? Here are two examples of approaches, neither of which are common ways of telling stories. The first example (shown below), and this is not a factual story, comes from the charity War Child Holland, a non-profit which aims to protect children caught up in conflicts, support their education, and equip them with skills for the future. This video shows an eight-year-old Syrian boy, Kadar, in a dusty refugee camp with a superhero playmate. The second example is the “See Me” campaign from St. John’s Homeless Shelter in Green Bay, Wisconsin, in which eight images, each with the words of an individual experiencing homelessness, were placed on city sidewalks in the summer of 2019. Three of these images are shown at the bottom of this post. “The guests who come to St. John’s are so much more than a singular identity of ‘homeless.’ Each person is someone’s son or daughter, each person has hopes, dreams, and qualities that make them unique,” says Alexa Priddy, St. John’s Director of Community Engagement. Physicians in many countries historically have taken the Hippocratic Oath as a rite of passage for medical graduates. In its most common form, it starts with: “First, do no harm.” I believe that when non-profit organizations, in the service of describing their programs and raising funds, depict individuals receiving services as only the sum of their problems, they are doing harm. This practice can further negative stereotypes of those in need. As is shown by the examples shown above, we can do better.

0 Comments

How do you connect with an audience that may be skeptical to the message which may come through as you use stories for awareness and/or advocacy? This is the second post on connecting with audiences, a follow-up to a post from June, 2019, in which I wrote on how to connect to audiences that are likely to be more receptive.

Connecting with an audience with individuals who are skeptical or who have beliefs that may be counter to yours is a daunting challenge. Once we have an opinion or belief about an issue, we tend to not pay attention to or give credence to information that contradict our position. Cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber call this myside bias,1 a type of confirmation bias, the cognitive process that leads people to either reject interpretation that goes against their beliefs or to interpret the information in a way that confirms these beliefs. Presenting information to change beliefs can lead to the backfire effect2 in which people may react to evidence showing that their beliefs are incorrect by strengthening their original position. When presenting information is not successful, stories may be. According to Michael Dahlstrom, there are two contrasting ways in which information is processed. As humans are natural storytellers, humans process information predominantly though narrative pathways, a more natural, efficient, and easy ways to process the information. He contrasts this with scientific processing, which is more challenging and requires analytical thinking skills to weigh, value, and make sense of the information. Dahlstrom uses the controversy over the safety of vaccines to show how these pathways compete: Vaccine proponents, he explained, often rely on scientific evidence to communicate the message that vaccines are a safe and effective way to prevent disease, whereas members of the antivaccine movement often share stories about dangerous side effects experienced by vaccinated children, which are processed as natural narratives.3 In the previous blog post, I mentioned three factors of a story and the way the story is told/communicated that are essential for the story to connect with an audience: Clarity: Is the story clear enough for the audience to understand as they experience it? Resonance: This includes emotional resonance (connection to emotions that matter to the audience), intellectual resonance (credibility), and what the marketer Debra Louison Levy refers to as “echo”—whether the narrative is similar in some way to others that are already part of the audience’s sense-making narrative. Something happens: Stories do not always have to be about overcoming conflict, but something has to happen. If there is learning/understanding or actions following this learning or climax, the story is more likely to “stick.” In addition to clarity, resonance, and something happening, stories in which there is a plot twist or an unexpected shift in the story may be more memorable. You see this in the memorable Agathe Christie novel, Murder of the Orient Express, made into a movie in 1974 and again in 2017, in which Detective Hercule Poirot finally realizes the question is not “Who done it?” but “How and why did a dozen passengers commit the murder?" I experienced the nature of the story shifting when I was I listening to a keynote speaker at a 2018 Poverty Conference. C. Nicole Mason, the dynamic Executive Director of the Center for Research and Policy in the Public Interest at the New York Women’s Foundation, was talking about her early life, growing up a in chaotic low-income single-parent family in Southern California. As I listened, I thought that this was going to be a rags to policy wonk story, about how she had made it to where she is today through her hard work and determination. Then she said: “Growing up, I knew many kids in my neighborhood who were smarter and more capable than me, and they didn’t make it out. Many of them have been killed, gone to prison, are living hand to mouth or otherwise on the margins of society. Should we blame them or the system that only allows a few of us at a time to escape?” She had changed the focus from her life as a singular example of how one can rise from poverty to a systemic examination of how the barriers, difficulties, and oppression in some communities make it hard for even smart and capable young people to be successful. In the terms of the FrameWorks Institute, she had changed the lens from portrait, a tight focus on an individual to landscape, viewing individuals in the context of their environment. Here is one approach to connecting with a skeptical audience. From time to time, I give story-based talks on poverty and homelessness to Christian education sessions at suburban churches in Southeastern Wisconsin. I recently read Ms. Mason’s 2016 memoir Born Bright: A Young Girl’s Journey from Nothing to Something in America 4. As I was reading this, I thought about how I might use Ms. Mason’s words and story in talking to an audience where everyone is “not singing from the same hymnbook.” There is a triangle, a three-part relationship which oral storytellers use to describe the connections between the teller, the story itself, and the audience. For an oral story to be effective, all of these connections need to exist. The teller needs to be emotionally connected to the story—there is something in the story that produces an emotional link. In addition, audience members need to be able to find common ground on some level with both the story and the teller in order for the story to resonate with them. In the section of Laura Packer’s book From Audience to Zeal: The ABCs of Finding, Crafting, and Telling a Great Story5 on connecting with an audience, she writes: “Love them where they are. If you love the audience in their current state, you are more likely to be able to connect with them.” While this applies obviously to the audience of an oral storyteller, I believe that it is also fits both to writing for and talking with a skeptical audience. When we think of an audience as composed of individuals whose opinions are wrong and need to be corrected, one is likely to preach to rather than connect with the audience. When we think of the audience as composed of people who are like us in some ways, we have a greater chance of connecting with them. Returning to my talking to a Christian education class in relatively affluent suburbia, in starting where the audience is, I might share my reaction to Ms. Mason's book. I would say that she had put her individual story in the context of the environment in which she grew up, in which the risk factors for minority youth were high, and the supports were minimal. As the Framework Institute points out, “If individual cases are not embedded in a larger social story, the public will see an issue as a private rather than a public problem, dismiss the importance of preventative approaches, or simply fail to imagine collective solutions.”6 I would also say that Ms. Mason’s success had much to do with the fact that from a young age she loved school, found it both a safe and nourishing place, even when the teaching was subpar and the resources inadequate. She won several awards for her writing and speaking through her school years and impressed and connected with teachers who mentored her, nourished her, and advocated for her. She was “born bright” and she worked hard, but her intelligence and efforts could easily have led nowhere, if not for a high school counselor with strong connections with Georgetown University. At that point, I would apply the “Yes, and…” technique from Comedy Improv, in which one agrees and then adds something to the discussion. Given that we understand stories through the lens of our own ideology and worldview, a politically conservative individual hearing Ms. Mason’s might think: “She’s the exception that proves the rule.” I would add my opinion that working hard is essential in doing well in any circumstance, and when we encounter situations in which smart, capable children who work hard have trouble succeeding, we need to see what can be done that raises the odds that they will become smart, capable adults. Yes, individuals have to work hard, and there are societal factors that can make that very difficult. Michael Dahlstrom7 states that previous research suggests that narratives may have a stronger effect on the acceptance of novel information over altering preexisting information. When we do not challenge an audience’s view of the world but rather suggest that an additional perspective is also needed (Yes, and…), I believe that the chances of our communication having an impact will improve. REFERENCES 1. Mercier, Hugo, and Sperber, Dan. (2019). The Enigma of Reason. Boston: Harvard University Press. 2. Effectivology. (2019). The Backfire Effect: Why Facts Don’t Always Change Minds. Retrieved from https://effectiviology.com/backfire-effect-facts-dont-change-minds/ 3. Dahlstrom, Michael. (2018) Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Understanding Narratives for National Security: Proceedings of a Workshop, pp. 13-19. 4. Mason, C. Nicole (2016) Born Bright: A Young Girl’s Journey from Nothing to Something in America. New York City: St. Martin’s Press. 5. Packer, Laura S. (2019). From Audience to Zeal: The ABCs of Finding, Crafting, and Telling a Great Story. Tolleson, AZ: The Small-Tooth-Dog Publishing Company. 6. Neil, Moira, et al. (2016) Strengthening the Support: How to Talk about Elder Abuse. A FrameWorks Message Memo. Washington, DC: The FrameWorks Institute. 6. O’Neil, Moira, et al. (2016) Strengthening the Support: How to Talk about Elder Abuse. A FrameWorks Message Memo. Washington, DC: The FrameWorks Institute. 7. Dahlstrom, Michael. (2010). The Role of Causality in Information Acceptance in Narratives: An Example from Science Communication. Communication Research, 20(10), pp. 1-19. |

Storying the Human Experience

Yes, it's a grandiose title. But, as Flannery O'Connor once said, "A story is a way to say something that can't be said any other way." Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed