|

Darcy Alexandra is a writer, ethnographer, and documentary storyteller specializing in audio-visual anthropology, digital storytelling and social documentary practices. She currently works at the Institute for Social Anthropology, University of Bern.

0 Comments

Tom McGowan is a chemical engineering whose consulting business takes him all over the world, and a raconteur. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

I remember being in Sunday School at the First Presbyterian Church in Bristol, Tennessee sometime during my third-grade year. One Sunday, as part of our lesson, we were given a two-page tale about a boy and a girl, in which they made a mistake and conveniently learned the lesson of the week. I still remember my visceral reaction in reading it--close to outrage. It was not a story, just a moral lesson dressed in narrative clothing for childhood consumption.

At that point, I could not have said what a story or a good story was, but I had been exposed to good stories since my earliest days. I grew up in a house filled with books, the child of parents with three graduate degrees in English between them. My parents read Blueberries for Sal, Make Way for Ducklings, Ferdinand the Bull, and many other books to me when I was young. I devoured the Narnia tales, Greek and Roman myths, and every comic book I could get my hands on. As an adult, while Social Work and college teaching have been my careers, stories have continued to be a significant part of my life. In the decade of the 1990s I was storytelling a good bit, in elementary schools, libraries, and bookstores. Now, the telling is occasional, mostly at story slams, but for the last nine years I have been working in the medium of digital stories--three-minute personal stories narrated by the story's author, with illustrative photos, video, and music. I create digital stories and help others to make them. I still couldn't concisely tell you what makes a good story. You can talk about the constituent elements of story-plot, characters, beginning-middle-end, conflict and resolution, and so on. I think back to what Bobby Norfolk said in the introduction to one of his storytelling performances: "All of these stories are true, and some of them actually happened." For me, what distinguishes whether or not a story rings true is if the story grabs me and won't let go, making me feel deeply and think hard about things, sticking with me long after I have hear/read/viewed it. There are tales told by storytellers that ring true for me--Jay O'Callahan's story of his uncle, a World War II chaplain who won a Medal of Honor in saving a ship and hundreds of men, and Elizabeth Ellis' retelling of the Demeter and Persephone myth, a version that incorporates the story of a daughter who was lost. There is Darcy Alexandra's digital story "Nowhere Anywhere," in which she wonders about the identity of her biological mother and experiences her verbally abusive father. Many of Shakespeare's and Arthur Miller's plays stick with me. The novel The Storied Life of A.J. Fickry and the movie Moonstruck are recently read/viewed stories that for me ring true. Stories challenge me, feed me, and enrich me. I'm Jim Winship, and I live in Southeastern Wisconsin and in the world of story. Brenda Rodriguez, a University of Wisconsin-Whitewater graduate and currently an elementary school teacher in Wisconsin, developed this digital story in 2014 in a three-day workshop in which college students each completed a digital story related to race, ethnicity, and/or justice issues. Jay O’Callahan is a phenomenal storyteller who performs nationally and internationally. He is best known for the long form oral stories which he creates and performs. In these, he uses the perspective of a central character to tell in riveting fashion the story of situations as diverse as the steel industry at its height in Pittsburgh and the decline of commercial fishing off the Atlantic coast. This 17-minute YouTube presentation is on the power of storytelling. In this presentation, he tells snippets of the story of NASA putting a man on the moon. To watch the 70-minute performance of Forged in the Stars, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EBIepu3tse An interchange one morning with a teenager in the house I lived in when in San Salvador with the Peace Corps in the early 1970s had stayed with me for decades, and working to make that conversation into a digital story helped me realize why it was so meaningful to me. Family stories sometimes are fun, sometimes nostalgic, and times they can be unsettling--but what are the ways in which family stories are important? This was the question that arose when I ran across Marshall Duke's research about how youth with a strong knowledge of family stories and family history tended to have fewer behavioral problems, less anxiety, and greater self-control than comparable youth who did not know family stories and history.

Dr. Duke conducted the study using a 20-question survey. Examples of the questions were: "Do you know how some of your grandparents met?" and "Do you know the national background of your family (such as English, German, Russian, Russian, etc.) [A full list of these questions can be found at the bottom of this post]. The research used widely accepted measures of family functioning, self-esteem, and locus of control, and showed strong correlations between knowledge of stories and these behavioral measures (1). So what does this mean? As Dr. Duke stated, the take away from the study should not be that parent introduce a home-based curriculum in which children and taught and then tested on family history information. The specifics of family history are, in many cases, embedded in stories, generally told in a family atmosphere in which there is open communication. Additional research indicates that the sharing of stories typically happens during holidays, family vacations, and family mealtimes (2). It is not clear how and when family stories are shared in families where shared mealtimes are less frequent and vacations rare. One explanation of Marshall Duke's research findings in that the knowledge of family stories can serve as a marker of open family communication. Aside from that, what about knowing family stories would contribute to overall well-being? In an interview, Dr. Duke's answer to that question was: "There are heroes in these stories, there are people who faced the worst and made it through. And this sense of continuity and relatedness to heroes seems to serve the purpose in kids of making them more resilient. Ordinary families can be special because they each have a history no other family has. They all have Uncle So and So, they all have Aunt So and So. They all have a brother who went off and did this adventure, and everyone has a story that no one else has. So if you know that, it makes you special. It's a fingerprint" (3). Knowing family stories can let you know how your ancestors made their way in the world and how they overcame adversity. In a course I taught, students wrote a paper about their ethnicity and their foremothers and forefathers. One student wrote: "I come from a line of strong Irish women." She saw herself as part of that lineage. That student was displaying what psychologist Robyn Fiyush categorizes as a sense of the intergenerational self. According to Fiyush, our identity comes form what we have experienced and also what we have been told. Family stories, including those of previous generations and of what life was like for the parent(s) before the child was born, create meaning beyond the individual, including a sense of self through historical time (4). A lack of family information and family stories is most pronounced for individuals who were adopted. For adoptees in closed adoptions, there is no knowledge of the birth parents and their families, leading to genealogical bewilderment, a disruption of the links between the past and the present. This lack of a connection between the past to the present can negatively affects one's identity, and may make it more difficult to envision the future (5). I go back to Robyn Fiyush: our identity comes from what we have experienced and also what we have been told. I would add that part of the power of family stories is that at times both of these are happening. The telling of well-known family stories as a family gathers can be a communal event, with children as well as adults adding in details of a story. However, it is important to note that while telling stories where the family's well-being increases over generations is relatively easy, telling the negative stories of a family is also important, and more difficult. If one is telling family stories to a child, not only the nature of the story but also the developmental age of the child has to be taken into account. Here is an example from my family. My wife's great-grandfather was murdered on the way home from a poker game in Ohio one night, probably killed by a cousin for the winnings. When he was in grade school, our son found the story fascinating and bragged about it to his friends. As he grew older, the story became more disturbing for him and complicated his thoughts about our family history. For, that family story is a close-to-home example about how a tragic event can debilitate a family over generations. I never shared my interpretation with our children, and I wonder how I could have done so when they were younger in a way that might have given them a better context for the story. I started this writing with the question: "What are the ways in which family stories are important?" Marshall Duke's research on family history and family stories is a partial answer to that question, and his study also does the same thing that a good story does. It points us in the direction of something worth thinking about. SOURCES 1. Duke, Marshall, Lazarus, Amber, and Fiyush, Robyn. "Knowledge of family history as a clinically useful index of psychological well-being and prognosis: A brief report." Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice Training. 45 (2008): 268-272. 2. Bower, G.H. and Clark, M.C. "Narrative stories as mediators for serial learning." 14 (1969): 181-182. 3. Kurylo, Elizabeth. "Profile: Marshall Duke." Emory Center for Myth and Ritual in American Life. (2013): www.marial.emory.edu/faculty/profiles/duke.htm. 4. Fiyush, Robyn, Bohanek, Jeffifer, and Duke, Marshall. “The Intergenerational Self: Subjective Perspective and Family History.” In Self Continuity: Individual and Collective Perspectives, Fabio Sani, ed. New York: Psychology Press, 2008, pp. 131-143. 5.. Affleck, M. & Steed, L. “Expectations and Experiences of Participants in Ongoing Adoption Reunion Relationships: A Qualitative Study". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(1), (2001): 38-48. DO YOU KNOW 1. Do you know how your parents met? Y N 2. Do you know where your mother grew up? Y N 3. Do you know where your father grew up? Y N 4. Do you know where some of your grandparents grew up? Y N 5. Do you know where some of your grandparents met? Y N 6. Do you know where your parents were married? Y N 7. Do you know what went on when you were being born? Y N 8. Do you know the source of your name? Y N 9. Do you know some things about what happened when your brothers or sisters were being born? 10. Do you know which person in your family you look most like? Y N 11. Do you know which person in the family you act most like? Y N 12. Do you know some of the illnesses and injuries that your parents experienced when they were younger? Y N 13. Do you know some of the lessons that your parents learned from good or bad experiences? Y N 14. Do you know some things that happened to your mom or dad when they were in school? Y N 15. Do you know the national background of your family (such as English, German, Russian, etc.)? Y N 16. Do you know some of the jobs that your parents had when they were young? Y N 17. Do you know some awards that your parents received when they were young? Y N 18. Do you know the names of the schools that your mom went to? Y N 19. Do you know the names of the schools that your dad went to? Y N 20. Do you know about a relative whose face "froze" in a grumpy position because he or she did not smile enough (or another apocryphal story)? Y N Molly Patterson, who teaches history at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, wrote, narrated, and produced this digital story in a three-day workshop I conducted in May, 2016.

This story is by Yvonne Healy, an actress and storyteller who performs Irish stories and personal stories all over the world: www.IrishStoryTeller.US She lived in New York City for years, and this story is the account of friends' experiences on that fateful day.

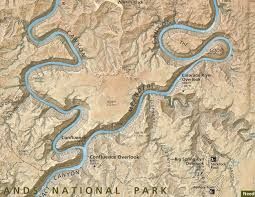

Humans tell stories. We are storytelling animal, homo fabulans, We know that other animals communicate, but it very well may be that we are the only species that tells stories. All humans tell stories ("You won't believe what happened to me while I was waiting in line at the store"). To varying degrees, we may all think of each of our lives as a story. The social psychologist Dan McAdams has conducted interviews over several decades with a range of individuals to understand how people see and understand their life. He concludes that in modern societies, by late adolescence to early adulthood, people begin to construct their personal past, their experience of the present, and an anticipated future into an internalized and evolving story of the self; this gives each one of us a sense of identity and coherence (1), According to the psychologist Jonathan Adler, we make meaning of our complicated existence by structuring our lives into stories (2). I stated earlier that to varying degrees we may all think of our life in terms of a story. I think that the degree to which a given individual does this varies tremendously. Novelists, who live in the world of plots, character development, and denouements, are more likely to think of their life in story terms. There is a quote that I have seen attributed both to Philip Roth and John Cheever: "My life is not my life; it is the story of my life." Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in his autobiography: "a man is always a teller of stories; he lives surrounded by his own stories and those of other people, he sees everything that happens to those other people, he sees everything that happens to him in terms of these stories and he tries to live his life as if he were recounting it" (3). For may part, and I admit that I am someone who lives in his head far too much, I find it useful to think about my life as a story. I think back to places I have lived, things I have done, instances and interactions, and I see some common patterns. I tend to loop back around or maintain a degrees of continuity with people, with places, with issues, and with ideas. For example, as I write this, a week ago I was in El Salvador. I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer there in the early 1970s, taught for half a year in a Salvadoran university in 2005, and have returned 20+ times since then, conducting research on youth and migration. For reasons that are not entirely clear to me, this small, wonderful country with far too much poverty and violence is part of my story, akin to a recurring character. I left full-time teaching 10 months ago. When I think about "What's next?"--I realize that I am embarking on another chapter in my life story. White there is utility in thinking of one's life in terms of a story, there are dangers. The map is not the terrain. Our interpretation of our our life events is built on our singular perception of those events. Someone who has felt misunderstood and discounted throughout life may look back from midlife and write: "As a child, I was alternately bullied and ignored, as my teachers and peers did not recognize my amazing abilities and gifts. Now as an adult, thanks entirely to my own efforts, I have been successful in many ways. I am sure that in the near future the world will realize and embrace my greatness." That way lies madness, or its first cousin, self-delusion. It can also be problematic if you think of your life as a relatively unchanging story, one in which all of the characters (including yourself) act in predictable ways. I think of the guy who found a note from his wife when he got home saying that she had left after 30 years of marriage. He exclaimed: "But we have a happy marriage!" The marriage was probably happy at some point, but people change, life changes, and the story needs to change with it. Staying with the example of marriage, a recent New York Times article included the same quote from several long-married individuals: "I've had at least three marriages. They've just all been with the same person" (4). In those cases, the couples realized that they were living in a changed and changing story. My life is not the story of my life, and the map is not the terrain. One needs a certain degree of self-awareness for considering one's life as a story to be a worthwhile perspective. But just as maps are valuable, showing possible journeys and lending an air of excitement to what comes next--as in the map of Canyonlands National Park above--so thinking of one's life as a story can yield both insight and energy for the road ahead. SOURCES 1. McAdams, Dan. The redemptive self: Stories Americans live by. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. 2. Quoted in https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/08/life-stories-narrative-psychology-redemption-mental-health/400796 3. Sartre, Jean-Paul. The Words. New York: Braziller, 1964. Quoted in Bruner, Jerome. Life as Narrative, Social Research, 2004, 71(4), pp. 691-710, p. 699. 4. From https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/21/style/modern-love-to-stay-married-embrace-change.html?_r=0 |

Storying the Human Experience

Yes, it's a grandiose title. But, as Flannery O'Connor once said, "A story is a way to say something that can't be said any other way." Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed